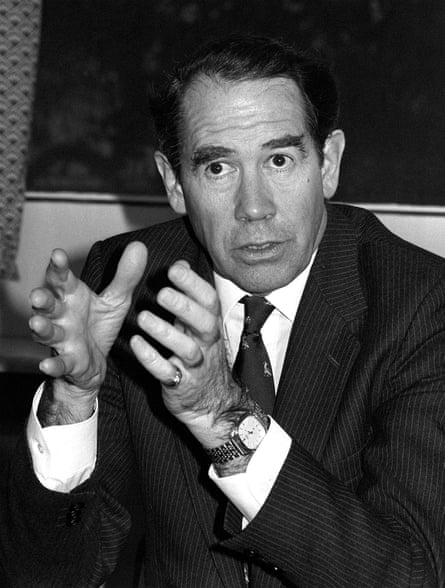

In August 1979 the cardiac surgeon Terence English, who has died aged 93, was poised to carry out a heart transplant at Papworth hospital in Cambridgeshire. If it did not go to plan, the operation, as well as being a tragedy for the patient, would end his vision for a Papworth heart transplant programme. Reminiscing at Papworth 40 years later, he said: “I very much had my back to the wall. I had a shot and I was going to take it.”

A heart transplant is the only lifeline for people with end-stage heart failure, and being able to carry out such an operation successfully had long been a goal for cardiac surgeons. Christiaan Barnard in South Africa performed the first human-to-human heart transplant in 1967, and between 1968 and 1969 Donald Ross carried out three in the UK, but the longest a patient had survived was 107 days. It was thought to be a false dawn, and in 1973 the UK chief medical officer put a moratorium on the procedure.

Having trained under Ross at the Royal Brompton hospital in London, English was determined that heart transplant surgery should not be mothballed indefinitely. He had come to Papworth as a consultant cardiac surgeon in 1973, and worked there as its cardiac unit director until 1995. In the 1970s he made several visits to California to learn from Donald Shumway, a world leader in heart transplants. He was also greatly encouraged in 1976 when the concept of brain death was formally recognised in the UK – a move that improved prospects for transplant surgery, because a donated organ from someone who was brain dead but with an intact circulation was more likely to be healthy and suitable for transplantation.

English and his Papworth team studied protocols, collected data, and in 1978 asked the Department of Health’s transplant advisory panel for permission to carry out heart transplants. They were turned down. However, English discovered Pauline Burnet to be sympathetic. She was chair of the Cambridge area health authority and agreed to fund two heart transplant cases at Papworth.

In January 1979 the first of these cases failed. The patient, Charles McHugh, went into cardiac arrest as he was prepared for surgery and he died from the ensuing brain damage. However, in August 1979, English’s second operation was a success. Keith Castle, an outgoing 52-year-old builder from London, lived for nearly six years, and he proved a tremendous ambassador for Papworth and for heart transplant surgery in general.

The public, many doctors (including some of English’s colleagues at Papworth) and the media had been hostile to heart transplants for years, framing it as a surgeons’ vanity project. But pictures of Castle living a full life started to win over public opinion. The National Heart Research Fund agreed to fund six more heart transplant operations at Papworth, and the programme gradually expanded. By the end of 1989 English had carried out 342 heart transplants, and in 2004 he was gratified to see hundreds of former patients returning to Papworth for the programme’s 25th anniversary.

He was knighted for services to medicine and surgery in 1991, and became president of the Royal College of Surgeons (1989-92), president of the British Medical Association (1995-96) and master of St Catharine’s College, Cambridge (1993-2000).

But high-status establishment roles were not enough for English. In his 70s he was passionate about making a difference in conflict areas such as Palestine and Pakistan, becoming a trustee of the Leonard Cheshire Centre for Conflict Recovery as well as the charity International Disaster and Emergency Aid with Long-term Support (Ideals). He was also a patron of Medical Aid for Palestine. In his last decade, English also supported Dignity in Dying, wanting to get physician-assisted dying legalised.

He was born in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. His father, Arthur, a mining engineer, died when he was a toddler, and his mother, Mavis (nee Lund), a nurse, moved the family to Johannesburg, where Terence grew up with his older sister, Elizabeth.

He boarded at Hilton college in Natal before working as a diamond driller in rural Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and taking a civil engineering degree back in Johannesburg at the University of the Witwatersrand. He completed his degree in 1954, but a family bequest of £2,000 changed his life. Influenced by his uncle Max Lund, a surgeon, he decided to use the legacy to go to London to study medicine at Guy’s hospital.

He had doubts about the course initially, and although he enjoyed captaining the Guy’s rugby team, he decided to quit and go to Canada to work in mining. But after a change of mind he successfully petitioned the dean at Guy’s to rejoin his course, and he qualified as a doctor in 1962.

English had a predilection for cars all his life – as a medical student he spent his £175 savings on a 1930s Rolls-Royce “to add to the pleasure of life”. In retirement he enjoyed making adventurous trips to remote parts of the world, climbing Kilimanjaro on his 70th birthday and driving from London to Cape Town and across India and China in his Toyota land cruisers. He retained his dare-devil spirit all his life, joining his son’s family on a Christmas Day swim in the sea in Cornwall when he was 85.

In 1963 he married fellow South African Ann Dicey, a nurse, and they had four children. They divorced in 2000 and in 2002 he married Judith Milne, principal of St Hilda’s College, Oxford.

He is survived by Judith, his children, Katharine, Arthur, Mary and William, eight grandchildren and his sister Elizabeth.

1 day ago

3

1 day ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·